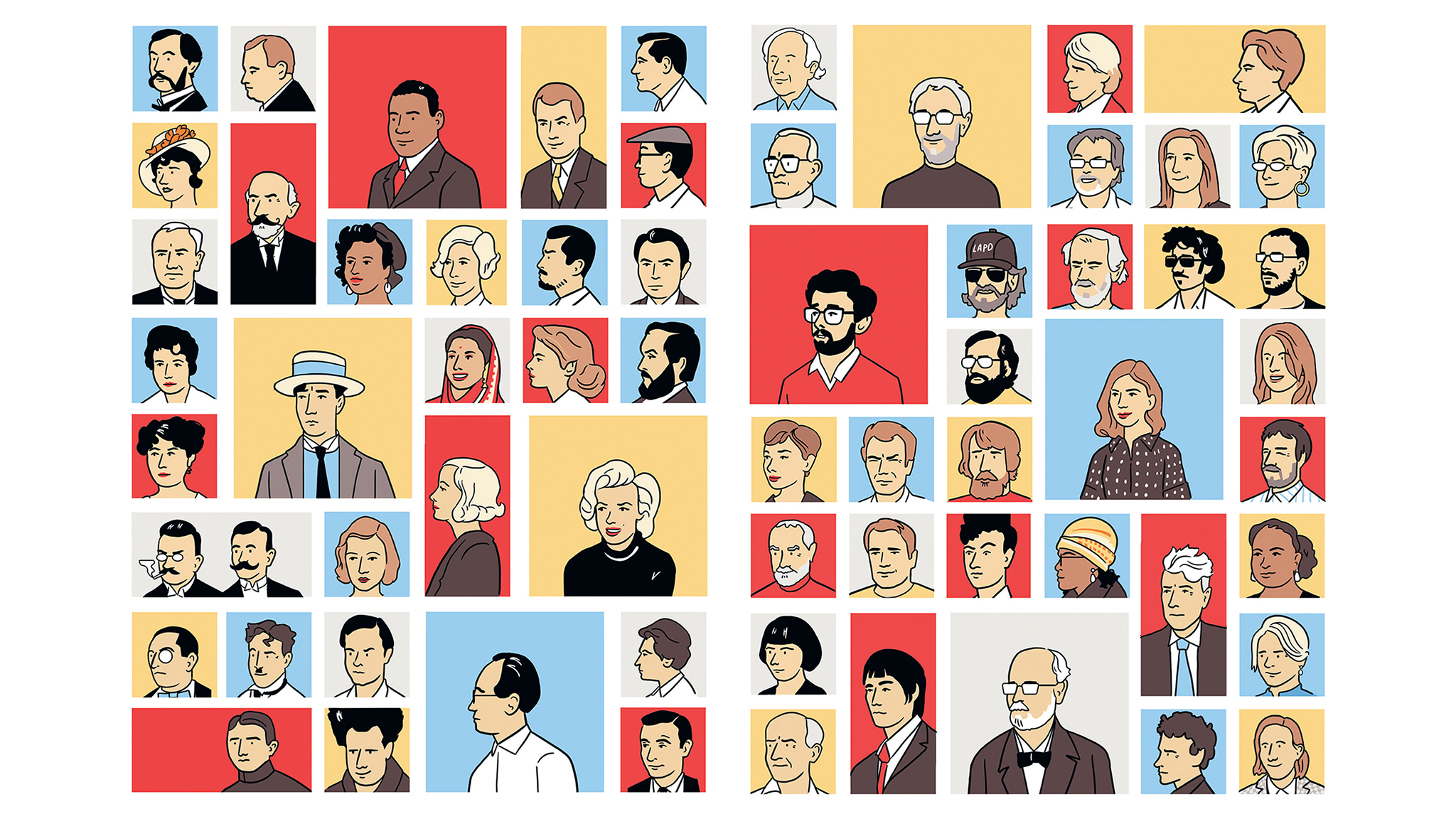

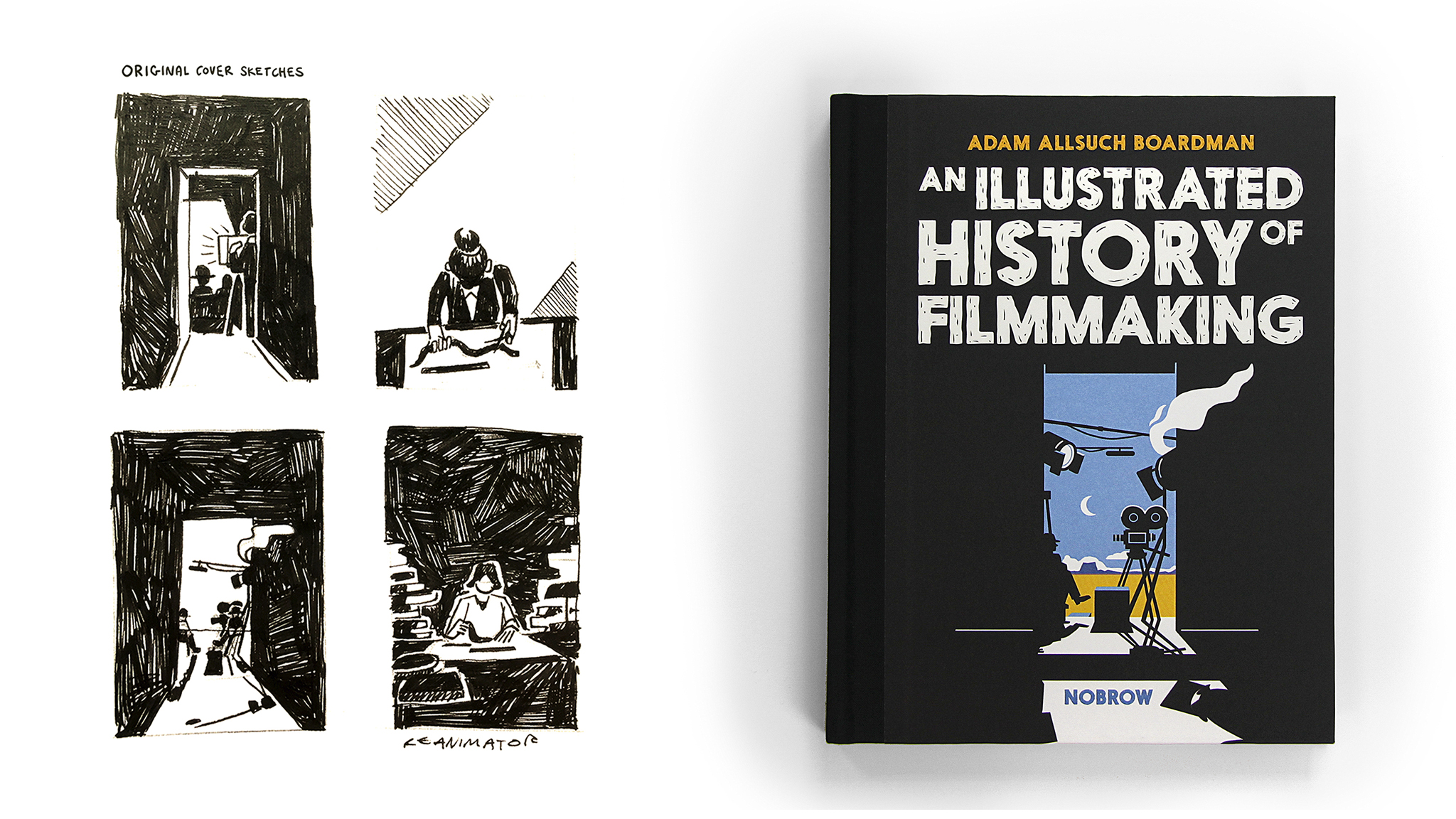

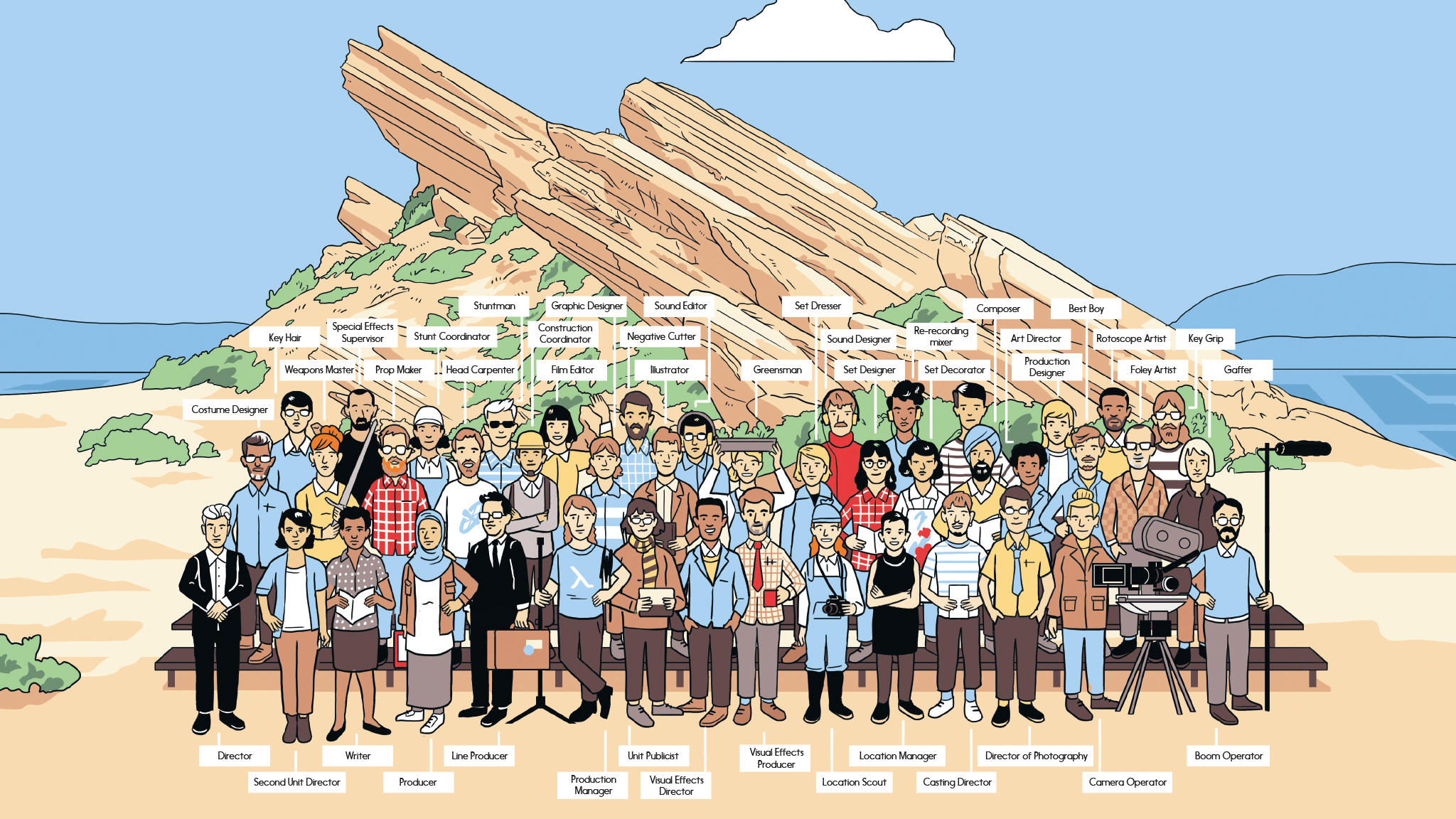

Infographics meet architecture in Adam Allsuch Boardman’s unique illustrations, which feature detailed line work with diagrammatic accuracy. Demonstrated in his latest book, An Illustrated History of Filmmaking, Adam leads us through the history of one of his favourite subjects. We caught up with Adam to find out more about his creative process as well as discussing his distinctive visual language.

Q. Where was your first port of call for your research?

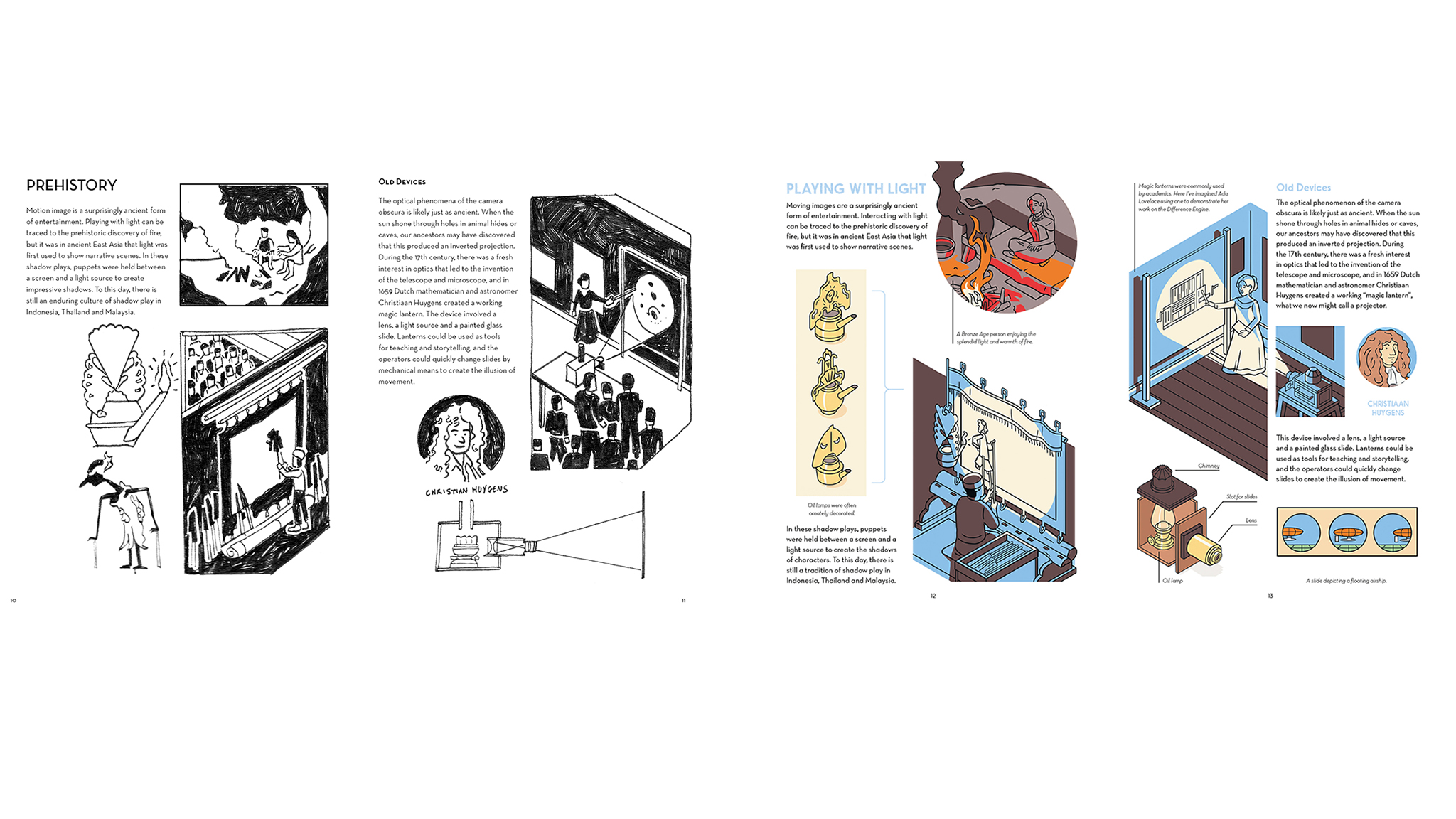

To begin with, I amassed a healthy stack of books from the library. Whilst reading, I would take notes and begin drawing my own cryptic diagrams for later reference. I found that the much older books tended to contain quite charming illustrations, which I would scan and study. I also watched a whole bunch of documentaries and DVD extras, and listened to podcasts. Absorbing different types of information helped manifest a much clearer idea of the book within my headspace.

Q. Was there anything you couldn’t include in the book that you would have liked to have kept in?

Q. Was there anything you couldn’t include in the book that you would have liked to have kept in?

Had I the time to spare, there were a lot of focussed catalogues of information I would have liked to take to the extreme. For example, I began drawing a lot of cinema ticket booths. I really enjoyed how a simplistic and functional cupboard-like room had been reinterpreted in such diverse ways over the last century of cinema architecture. It’s honestly something that’s deserving of its own book!

Q. Your work is quite diagrammatic. What were your main influences as this style progressed?

When I first started out with illustration, I worked frequently with museums and on educational projects. This led me to interpret imagery in what I find is the most literal sense. I like to show the space of things in an easily understood way. The use of clear line has interested me since childhood, having learned to read with the assistance of Hergé’s Adventures of Tintin. I also have a deep fondness for the clarity of illustration present in school exam papers and revision materials.

Q. You have a distinctive way of using perspective in this book. Was this a conscious design decision for this title, or is this something you have been leaning towards?

Q. You have a distinctive way of using perspective in this book. Was this a conscious design decision for this title, or is this something you have been leaning towards?

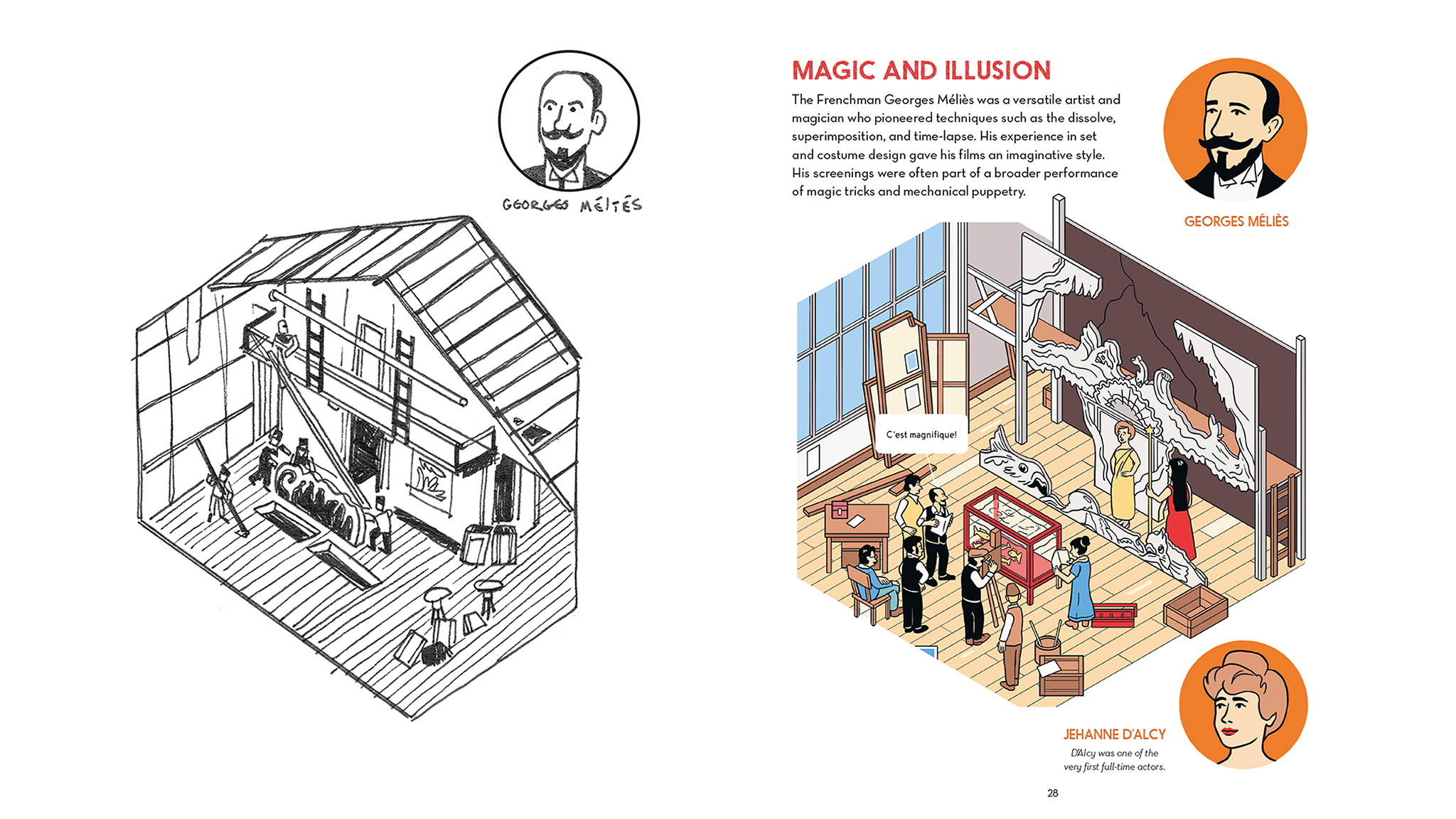

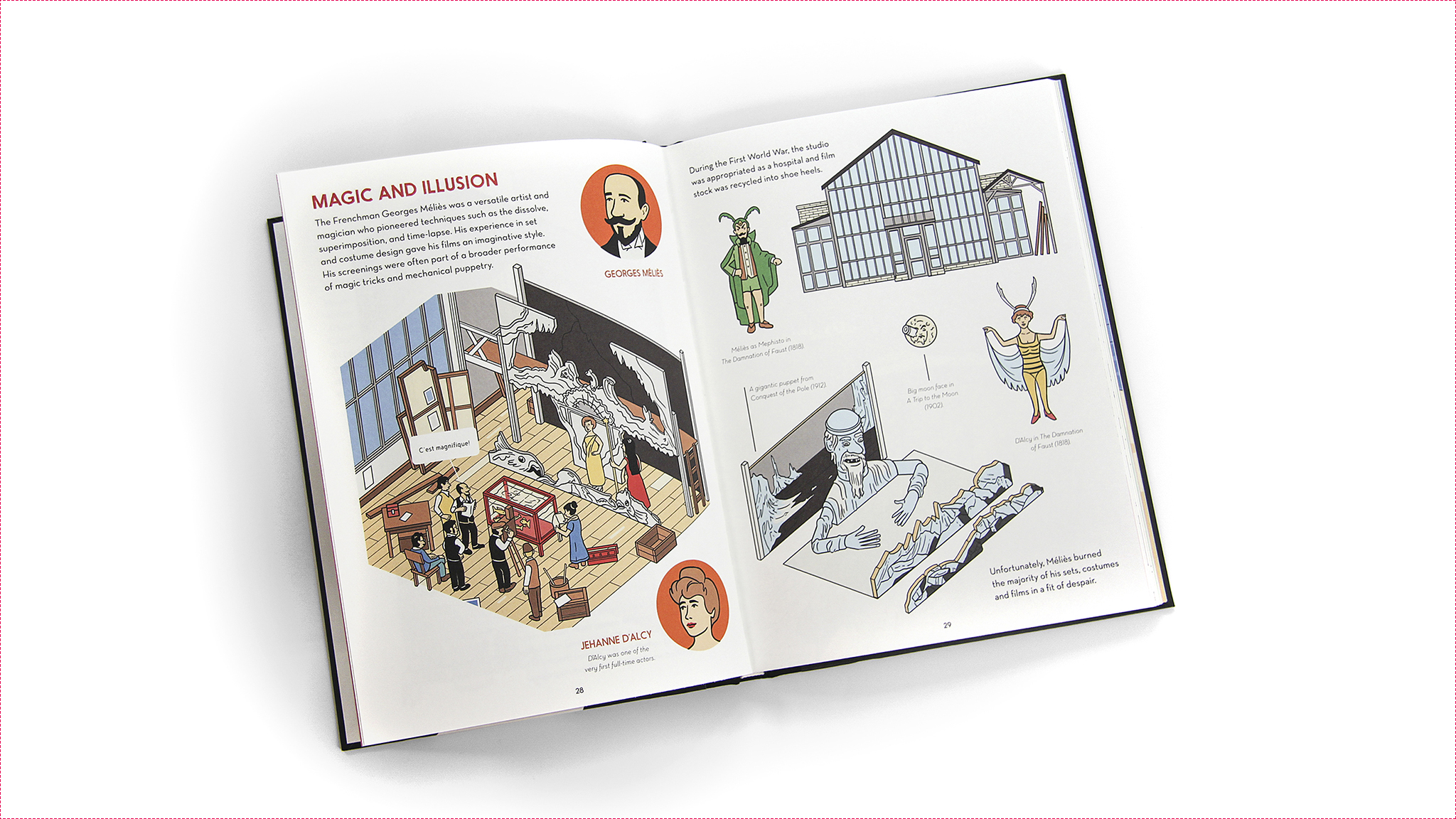

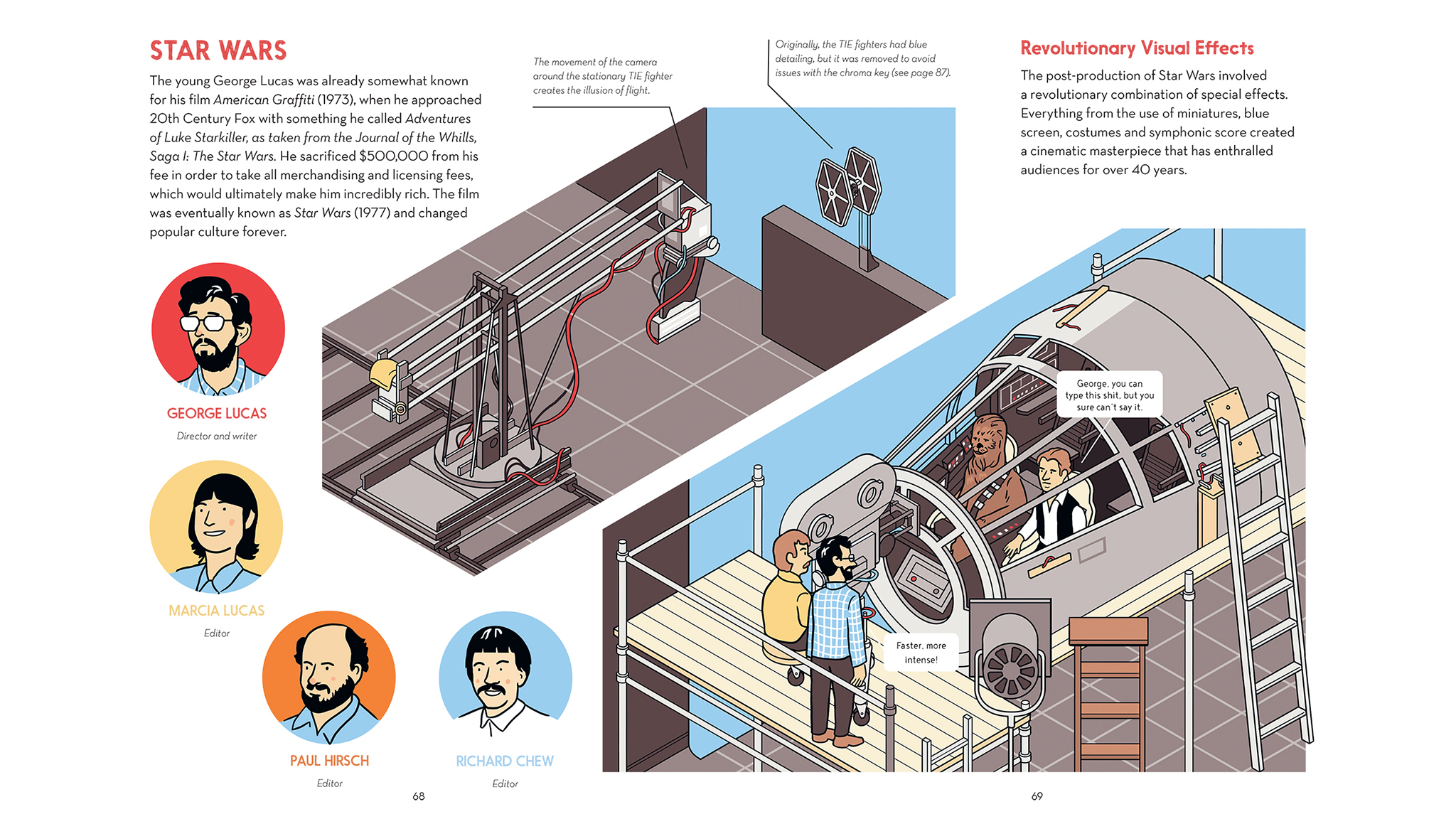

I find that clarifying an object into a more impartial isometric perspective is very satisfying. The process of repeatedly and obsessively studying an object can be a lot of fun; often the rarer objects can send one down a bizarre rabbit hole of books and websites, just so one can find a better angle of reference… or indeed to go visit a museum solely to see a particular artefact.

Q. If you had the choice to dedicate several pages of this book to just one individual in filmmaking, who would it be and why?

It was incredibly hard not to babble on at length about each filmmaker, and there are so many fantastic lives both in front and behind the lens. I find folk like Jehanne D’Alcy really interesting – as one of the first full-time film actresses, she must have had a really unique experience of the industry, especially during its fledgling years.

Q. Are there any directors or cinematographers whose artistic direction has influenced your own work?

It’s often difficult to put an aesthetic down to one particular person – it’s a team effort after all! But Kazuo Miyagawa and John Alcott are some particular chaps that I find really grand. Many shots in 2001: A Space Odyssey continually amaze me. I am also astounded by the imagery of How the West Was Won. The unique camera trickery that made Cinerama work means that every single frame of information is divided into thirds, which creates a very unique visual language. By most accounts it was a nightmare of a system for everyone involved, but it looked fab.

Q. What was your favourite part of the book to write/illustrate and why?

Q. What was your favourite part of the book to write/illustrate and why?

One of the more trivial details of the book was the need to include furniture and fashion tied to the context of its time period. This included heaps of tangential research that I really enjoyed. In particular I loved looking at 1970s shirts.

Otherwise, the more grand and detailed isometric scenes such as the Vaudeville and orchestral recording were images that I spent a large chunk of time and concentration on. I found it most enjoyable to truly inhabit an imaginary space and flesh it out with believable detail based on various photographic and illustrative references.

Q. If you could do an Illustrated History of anything else, what would you choose and why?

In the intro to An Illustrated History of Filmmaking, I outlined that I deliberately left out animation, as to include it as a tacked-on chapter would have been an absolute disservice to its important role in entertainment. So, I would love to celebrate the history of animation with its own book following much of the same structure, highlighting some of the key folk, events and technology that made it all possible.

Otherwise I have a long list of subjects that I desperately want to conjure into the format of a book. Ufology for one – it would be particularly fun to draw and write about!

Get the book here!